The old woman walked between the dusty barracks to the office, and in the back of the office there was a door, and behind that door sat a smiling man, with bright red cheeks and hair like a baby’s.

“The war will be over soon,” he told her. “What will happen to you then? What will happen to everyone here?”

She did not answer him. She was too surprised that he was speaking in Japanese.

“There is another world beyond this dusty camp. In that world, loyalty will be rewarded. Everyone who comes with me will get back everything they lost, and more,” he continued.

She waited.

“I can offer safe passage to two members of your family,” he said.

“There are four of us in my family.”

“You are an alien,” he reminded her.

“I have foresworn any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor,” she said. “And my daughter and her two children are all loyal citizens.”

“I can offer passage to two of you,” he said, still smiling. “I want to help.”

He waited.

“The boy, and his mother,” she said. “The girl will stay with me.”

He told her to come back before dawn. She walked back through the barracks. Her daughter and the children were still out when she returned, so she opened her trunk and reached around at the bottom. She removed a slim, yellowing envelope, and closed the trunk again.

* * *

1 Piano 12/10/45

1 Piano stool, 1 leg broken and missing Mrs. Benson present

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx when piano was picked

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx up. Stool was broken

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx 1 leg missing.

* * *

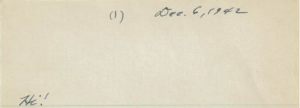

It is late evening, Dec. 6, 1942, and a young college student, George Inouye, is writing a letter to his family. He writes more often than they write back, because his life is changing so quickly, while theirs is the same, day after day. He writes to them whenever he can.

His family is being held at Tule Lake. That fall, George Inouye left camp for Swarthmore, one of 402 college students selected for relocation to schools in the Midwest and East Coast. An elite and carefully vetted group, they bore responsibility not just for themselves and their families, but for several thousand other students who would follow their path, and eventually, for all the other resettlers who’d be sent east through various efforts to empty the camps.

“It might have been an interesting experiment in socialism,” he writes of Tule Lake, “had everyone there been there voluntarily & were interested in working for the common good, but under the present conditions, I have my doubts.” Although the decision to round up Japanese Americans merely extended a long tradition of anti-Asian racism—think exclusion movements, laws against property owning and interracial marriage, mob violence—the actual administration of the camps was different.

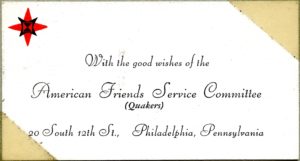

Many in the WRA felt themselves motivated by genuine concern for their prisoners’ well being, and worked closely with the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council (NJASRC) and the Quakers’ AFSC, while elevating the controversial, nisei-led JACL as the community’s voice. A commitment to resettling inmates and redefining Japanese Americans’ public image became central to the WRA’s institutional mission. Indeed, many officials believed that their interesting experiment would not merely rehabilitate their charges, but actually make them better Americans.

In short, the WRA regime was less a part of prewar exclusionism than of the earnest, paternalistic racial liberalism of the postwar period. The origins of the “model minority” myth lie behind the barbed war of a concentration camp. The process of rehabilitating the Japanese American citizen—loyal, quiet, steadfast—continues to this day, and between the violence of forced removal and imprisonment and the violence of resettlement and rehabilitation, it is difficult to say which is the greater trauma.

While a bright young nisei like George Inouye might have had doubts, he was not going to miss an opportunity—which he ascribed not to government benevolence, but a higher power. He’d found a new belief in God, and a new purpose in what he’d once expected would be an “insignificant, inconsequential” life: “How else is it possible that I could be here in such a wonderful college in such a time when I hadn’t even hoped to attend U.C. in a year?”

This was the great and terrible irony of the new life the nisei found in Philadelphia: it was better than the world they’d left for camp.

The old-fashioned racism was still there, of course. One resettler, Kazie Good, recalled how a group of kids smeared her little sister’s ice cream cone all over her face, and cut off her hair, and that her brother, still in his army uniform, was refused service by a barber. Five resettlers out of Gila River came to Philadelphia from a farm in Great Meadows, NJ, where they’d been run off by arson and mass protests, endorsed by the governor. To show there were no hard feelings, neighbors threw a party for the young white farmer who agreed to fire the men, and took down the signs near his farm that read, “Little Tokio—One Mile.” George Inouye’s own fortunes had turned, but he “shudder[ed] to think” what postwar life would bring to most Japanese Americans.

Still, for the most ambitious nisei, opportunities for advancement that had been blocked on the West Coast were suddenly opening. George took a PhD in physics at Harvard, and his brother William and sister Miyoko followed him to Swarthmore and became physicians.

Like Mary Watanabe, Kazie Good majored in biology and chemistry and took a job in research, then returned to school after marriage. Hoping to match her work schedule to her children’s, she took an education degree, and taught elementary school and, later, ESL. William Inouye went on to invent a dialysis machine and make his name as a surgeon, although an early job as a chemist in an asbestos factory led to the disease that killed him, four decades later.

Miyoko and her husband, David Bassett, maintained joint careers in medicine, research, and university teaching, while becoming Quakers and dedicating their lives to social justice. In an op-ed column invoking Miyoko’s memory against President Trump’s Muslim ban, her son David Jr. revealed that she divided her $20,000 government-issued redress payment equally between Swarthmore and the AFSC.

Life after camp was never less than a miracle. But as in all new worlds, the price of passage remains a question you live with even beyond death.

* * *

DESCRIPTION OF ARTICLES

(Observe strictly carrier’s freight classification. Avoid trade or

technical names.)

“Non-Military”

Personal Effects

x 1 Trunk (Dark olive—square type),

x 1 Trunk—wardrobe, 1 Crate—Sewing

x machine (Singer foot-pedal), 1 Crate

x Sewing Machine (Singer—electric) with

x Tools, 1 Crate—table & chairs,

x 1 Crate—violin and Saxophone, 1 Box—

x books, 1 small box—canned goods, 1

x med. box—beddings, 1 box—personal

x effects, 1 large box—kitchen utensils,

x 1 large box—beddings & rugs, 1 small

x box—tools 1444 lbs.

* * *

Reading George Inouye’s letter three-quarters of a century later, what’s most striking—besides the page after page of narrow cursive handwriting—is the curiously detailed, almost compulsive way he rehearses the family’s shared experiences of the days and weeks after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. His memories come in a rush, punctuated with questions that anxiously seek confirmation, beginning with the night that changed “the whole pattern of [their] lives.” What were they doing? (A welcome-home party.) What did they eat? (Turkey.) Why did their parents argue? (Because their mother “kept claiming that she didn’t understand what ‘attack’ meant.”) Time begins to blur:

remember how the reports that people we knew were being picked up by the FBI began coming over our radio? Then those months—terrible months—of expectations—waiting—wondering when our turn came next—when we would come home from school & find pop gone, or find the FBI searching our home. Then all the books and papers we burned; I guess I & Pop & Miyo took the ash out of the stove almost every day & we were glad that it was winter so we could burn the stove.

Their future pays a visit, in the pages of a magazine: “Remember how curiously we looked at those pictures of Manzanar in ‘Life’?” Attempting to be practical, they stock up on supplies—“jeans & boots & dried vegetables & milk”—but the future doesn’t return.

And then it does:

The order came about Fri. May 15, maybe Thurs. & we left home on the next Fri. the 22nd. Boy we really packed didn’t we? And the store—we didn’t get rid of it till Wed. Willie, remember how we sold? It makes me sick to think about it. $35—$5, or say $4 and they’ll say 50¢…. Well, we were glad to get 300 for the store.

He agonizes over dates and numbers like he’s preparing for an exam, or an interrogation.

Then we were in Walerga. When we first got there it seemed like a picnic—all our friends there crowding around. Then the adjustments we had to make—living in a single room, common mess hall, latrines, etc. Well, pop sure made up for lost sleep too didn’t he?

“Pop” was Saburo Inouye, born in Hiroshima in 1888, and arrived in the US in 1914. He earned enough to return to Japan in 1919 in person to marry Michiyo, whom he brought back to Sacramento. In the US, he worked his way up from houseboy to fruit picker to owner of a restaurant, dry-goods store, and, finally, a furniture store big enough to support four families. He also repaired furniture, and collected antiques as a hobby.

When the nisei were older and had children of their own, they sometimes downplayed incarceration, saying it was just like summer camp. Later the sansei identified this as the repression of a trauma, which it surely was—though when the sansei had children, they’d learn to keep secrets of their own. Even so, it must have been a curious thrill, for the younger inmates, suddenly transported to a space between worlds—full of their friends, the authority of their parents dissolving, “a socialistic society if there ever was one.” Saburo saw a lifetime of effort reduced to $300 and took the opportunity to catch up on sleep.

George’s chronicle reaches an abrupt close, as they leave the temporary detention center for a permanent camp: “Then Walerga fades out & we reached Tule Lake. You’re still there & I’m here at college.” Life in camp, as he’d noted , leaves little to report: “I take it that camp is the same as it ever was—the same routine day after day.” The point is less that nothing ever happens in camp than that every day in camp can be exchanged with every other. Time sits still, and narrative ceases to function.

The key to George’s letter is in that line: “You’re still there & I’m here at college.” He goes on to reflect and speculate about the future, but this is where his painstaking efforts to set down and verify his family’s shared experiences stops. What’s going on here?

If you encounter this letter as a historical document, it’s easy to imagine that George is writing for the archives, trying to commit to memory what happened, and how it felt. Or, if you seek to understand the consequences of camp, its ongoing reverberations across the time and space of multiple worlds, it makes sense to describe George’s writing as the involuntary repetition of a trauma.

But I think what’s happening is simpler: he is afraid that he’s left his family behind for good. They are there, and he is here, but he’s trying to remind himself that he’s still one of them, and to convince them that he hasn’t forgotten them—even though the very condition of George’s life in this dazzling new world is to go through the day as if Walerga and Tule Lake never happened.

He is trying to be in two places at once.

It grows late, and George’s letter for the day draws to a close, at 1:15 in the morning, the calendar now flipped to Dec. 7, 1942. As if an aesthetic spirit possessing his pen had planned it that way from the beginning, he runs out of paper as he signs his name on the very last line: “This is the last sheet in the tablet I brought from Tule Lake.”

* * *

8. Since I have not seen my personal effects and other property for a considerable time and have no reliable inventory thereof, I hereby delegate the War Relocation Authority as my agent to cause an inventory to be taken of the property which I am requesting the War Relocation Authority to transport for me. I have confidence in the integrity and good intentions of the War Relocation Authority and its representatives, and I hereby agree to accept as correct, subject to any claims I may make in writing within 10 days of my receipt of such list, the list which will be delivered to me by the War Relocation Authority to inform me what goods are being or have been transported for me.

* * *

In the “Power of Words Handbook,” a 2013 publication, the JACL attempted to codify a series of terminological changes long sought by activists. Against established euphemisms like “evacuation” and “relocation,” “assembly center,” and “relocation center,” the JACL insisted on more accurate terms: forced removal, temporary detention center, and American concentration camp. Even the once-familiar “internment,” whose legal definition refers narrowly to the wartime confinement of enemy aliens, is abandoned for the more encompassing incarceration.

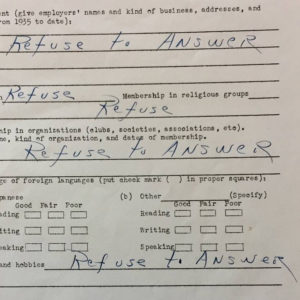

Arguably the most blatant of the government’s euphemisms, “non-alien,” is rejected for the term it meant to deny, U.S. citizen. But it is here that I hesitate. The nisei, by birthright, were indeed citizens, but that status did not carry with it the inalienable rights it claimed. A non-alien is a double negative, like the “no-no boys” so-called for their answers to the notorious questions 27 and 28 of the WRA’s loyalty questionnaire; not-not a citizen, she is an unaccounted hybrid, a variety of alien homegrown on US territory. The whole process of Japanese American rehabilitation, begun in camp and extending, unfinished, across all these decades, is founded on the disavowal of the non-alien’s existence, her repression and the denial of her name.

Simply put, the non-alien is a US citizen whose rights are cancellable on racial grounds. When the camps closed, she may have disappeared, but she never left, and nowadays her numbers are increasing. What would it take for the non-alien to be free?

* * *

The sun had not yet shown its face above the desert when the family assembled at the designated meeting point. The young mother, hardly sure she was awake, rubbed her eyes and looked at the smiling man. “You aren’t with the WRA, are you,” she said.

It was not a question, so he did not answer, instead leading them on a brisk walk through the barracks to a small building that none of them could recall seeing previously. It was a wooden structure raised above the ground by the height of three cement steps and was barely larger than a closet. There was a hole in the ground beneath it, which seemed to be glowing.

“Is that an outhouse?” the boy asked.

The smiling man did not answer, but turned to the old woman and said, “It would have been better if you had said your goodbyes in your apartment.”

“Where are we going?” asked the boy, now bolder.

The smiling man crouched down. “You and your mother are being evacuated, for your own protection.”

“What about them?” he asked, looking at his sister and his grandmother.

The smiling man stood up, and looked at the old woman. “It is time. The mother will go first.”

Quietly she stepped forward, climbed the steps—one-two-three—and opened the door. When she closed it, there was a sound like a swarm of insects, all rising at once. The children did not cry, but only pulled closer together.

“And now it is your turn,” said the smiling man to the boy, his voice gentle as a teacher’s.

Releasing one hand from his sister’s, the other clutched in his pocket, the boy did as he was told. Her hand was in her pocket too. Then one-two-three—the rush of tiny wings—and he was gone.

The girl flickered, and disappeared too.

The man turned sharply to the old woman, his smile broader, his eyes flashing. “I told you there was only passage for two!” he whispered.

“They are twins,” she told him helplessly. She would not begin to cry until later, lying alone in the barracks, an empty envelope beneath her head, wondering if she had done the right thing.

* * *

1 Pair small opera glasses 3-1-46

1 Pair opera glasses #13334 Picked up at Sac’to

1 Japanese sword Police Dept.

1 Repeater shotgun — Spencer Mullins

1 Radio allied #221A-4459

* * *

The Inouye children were a formidable bunch. William followed George to Swarthmore first, while Miyoko initially stayed behind with her parents, seeing them through the move from Tule Lake in California to another camp, Jerome, in Arkansas. After an infamous WRA questionnaire attempted to separate out “loyal” inmates from “disloyals,” Tule Lake was designated for the latter. The children petitioned the resettlement bureaucracy to find work for their aging parents in Philadelphia, while simultaneously working to convince them—really, to convince Saburo—that it would be better to leave camp.

On the whole, it’s fair to say that incarcerated Japanese Americans essentially lost everything, departing for camp with only what they could carry. Every family has a story, from the Inouye’s $300 to the little red wagon that a nine-year-old Herb Horikawa, who eventually resettled in Philadelphia from Poston, left behind in Watsonville. The morning that Kazie Good left Sacramento, she found a young boy sitting on her porch, waiting for the model airplane that her brother had promised him. It had a little engine. Her brother had saved up his money for it, and built it, but he never saw it fly.

My own family tells a story about my great-grandmother’s house in San Diego, purchased in my grandfather’s name because of the laws preventing Japanese immigrants from owning property. While he was in the army and she was in camp with her younger children, their land was condemned for a government project. The tale goes that the entire house was stolen, lifted off its foundations and hauled away, never to be seen again.

The experience, as George Inouye had noted, also encouraged experiments in socialism. Herb Horikawa’s future wife, Miko Asaki, got a bike while her family was resettled at Seabrook Farms in New Jersey. It was a girl’s bike—a light blue Schwinn—but everybody at Seabrook learned to ride on it. One of my grandfather’s brothers brought a bike to Poston, and it was the same there.

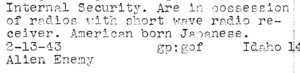

Despite all this, the government did put some formal procedures in place whereby the most assiduous incarcerees might attempt to store and recover some belongings. The Inouyes were assiduous. William sent letter after form after letter across the country from Philadelphia, seeking the return of items they’d been required to surrender to the Sacramento Police Department—some Japanese swords, a 19th-century shotgun, flashlights, opera glasses, kitchen cutlery, a radio, and cameras. He was very persistent about the cameras. The issei and nisei both were mad for photography.

Eventually the WRA offered Saburo and Michiyo the opportunity to rejoin their children, inviting them to run a hostel for resettlers at 3228 Chestnut Street in Philadelphia. More than two dozen resettlement hostels, scattered across the Midwest and East Coast—from Kansas City and Des Moines to New York City and Boston, and from St. Louis to Minneapolis—were sponsored by the AFSC and other churches and social service organizations, working closely with the WRA. The first hostels opened in spring and summer of 1943, in Chicago, Cincinnati, and Cleveland. More hostels opened in 1944 and 1945 as the end of the camp regime came into view.

By the end of 1946, most of the hostels had closed, and by 1949, only the Philadelphia location remained, now at 4238 Spruce, because the industrious Inouyes, given the opportunity to purchase the building, had transitioned to serve international college students. In 1968, at the age of 80, Saburo died, but Michiyo hung on until 1974, retiring four years before her own passing at 79.

In camp, Saburo had seen his fortunes fall, from small business owner back to steward, farm laborer, and office help, but Michiyo had served as a nurse’s aide and dietician. The latter fact was often touted in promotional literature sponsored by the WRA, as Michiyo’s duties included shopping and cooking for the guests. At one point, she even took a cake decorating class. Saburo was the handyman and gardener, and went to the train station to pick up new arrivals. His skills at furniture repair and general facility with tools was often mentioned as well. The couple’s duties also entailed counseling residents with “personal problems.”

By the early fifties, when the law allowed it, Michiyo became a citizen. Saburo, for reasons he seems to have kept to himself, did not go through the trouble. On the 68th birthday of Emperor Hirohito in 1969, the year after Saburo’s death, Michiyo was recognized with the Order of the Sacred Treasure, sixth class, presented to her at a ceremony in New York by Consul General Yasuhiko Nara.

How far had life taken Mrs. Inouye, in those twenty-five years from Walerga, Tule Lake and Jerome! Her children were exceptionally successful professionals, she was running a successful business on her own, and, as a U.S. citizen, she found acclaim in her adopted country for an award from its erstwhile enemy, the Emperor of Japan. I cannot begin to take the measure of all that she lost, and all that was given to her in its place.

Her husband was dead. Whatever else Saburo gained or lost in his life, his later years were spent in the company of family, in relative comfort. Photos from those years show him laughing with grandchildren, a proud father next to a man in cap and gown, carving a comically large turkey, sitting on the stoop examining what could be a camera or a radio, at ease on a beach with Michiyo, binoculars (“opera glasses”?) in hand. He must have renewed his old hobby of antique collecting, for his grandchildren still keep a dazzling old “gong”—a set of four metal temple bells with a beautiful pattern of leaves and flowers, hung one below the other in decreasing sizes—which they say was used as a dinner bell at the old hostel.

In all his years welcoming new arrivals to Philadelphia, Saburo must have had plenty of occasions to see that old bell they’re so proud of, the one with a crack in it. I wonder what he thought of the sight. I want to say that the Inouyes don’t seem like the kind of people who’d make things that crack, but this world has a way of shattering even the most careful plans. I should say, instead, that the Inouyes seem like the kind of people who wouldn’t let a crack go long without fixing. In his years at the hostel, Saburo took his tools and he fixed things. I want to believe he found some satisfaction in that.

* * *

2 Japanese swords

x ) These two cameras

1 Camera — Eastman Vest Pocket Folding ) could not be located

x ) by the Police Dept at

1 Camera — Baby Brownie ) time of former pickup.

2 Small cleavers ) This lot was picked up

x ) for evacuee at his re-

3 Flashlights — used ) quest in a letter given

x ) to Police Dept. by Mr.

1 Odd lot of seven miscellaneous knives ) Mullins. Receipt for these

x ) articles was issued to

5 Paper boxes of kitchen knives ) S. Inouye & R. Yeya by the

x ) police Dept. 2-17-42, Re-

1 Wood box containing set of kitchen knives ) ceipt #2947. 1 wide knife

x ) and 2 flashlights could

x ) not be located by Police

x ) Dept. Receipt is re-

x ) turned attached to evacuee

x ) copy of E.P.R.

* * *

![]()