In their new lives in this Eastern city the boy and his mother do not speak much. The other new arrivals seem to take immediately to the atmosphere, as if the bustle and shine of the streets was their own long-promised homeland, its secrets already memorized, recited nightly under thin, rough blankets in the desert. They speak faster now, their voices clipped, wise, glinting.

In those first days, the boy had filled his mouth with sweets, and now his tongue felt like it was pulling through swampy water.

The others all seem to know where to go to find work, but the young mother is too frightened to ask them any questions. So she spends her days dragging the boy around downtown, staring blankly into shop windows. In camp, she’d passed the days flipping through mail-order catalogs, a habit that seemed to calm her. But on their window-shopping excursions, the boy would sometimes look past the crisp shirts or gleaming leather shoes and see an old red wagon, or a model airplane, the paint accidently dripped behind one wing, just so, and he’d squeeze his eyes shut, refusing to walk any further until his mother agreed to take him back to their room.

He was glad that his sister had come to this city with them, but he wasn’t ready to see her yet.

* * *

* * *

“NEWS FROM PHILADELPHIA!”—the exclamation point, as sunnily earnest and wryly self-deprecating as the nisei themselves, is an essential detail. Eight mimeographed pages, a newsletter, dated October 25, 1943. Sent out to the camps from the WRA office in the Stephen Girard Building on South 12th Street, it is signed by Henry C. Patterson, Relocation Officer. This is the man to see in Philadelphia! A liberal Republican and a Quaker deeply committed to humanitarian work in race relations, Henry Carter Patterson was a lifetime membership subscriber to the NAACP, and would serve as the first Philadelphia director of the United Negro College Fund. He corresponded with Nixon during the latter’s vice presidency, and advised Wendell Willkie on the pursuit of the black vote.

A month earlier, after William Inouye and his siblings had sought the assistance of the WRA in relocating their parents to Philadelphia, it was Patterson who took up their case. Mary Patterson, his wife, also exchanged letters with Miyoko and Michiyo as they worked to overcome Saburo’s reluctance to resettle. By the following February, Henry was arranging for Michiyo and Saburo to stop over in Cincinnati, to assist at the hostel there while waiting for their position in Philadelphia to open.

In his prose, Patterson shows an eye for incisive detail and an understated verve, which recalls the great nisei writer Hisaye Yamamoto. Patterson clearly took pleasure in crafting his little mimeographed missives to his distant readers in those desolate camps, and you might be tempted to call them the work of a frustrated novelist—except that there isn’t a trace of frustration to be found in his affable writing. And that’s the difference between his voice and Yamamoto’s. In hers, you hear the quiet, sometimes wicked chuckle of a talent that has made its peace with being underestimated, while his shines with a genial knowingness that lingers over human foibles as if they were proof, in themselves, of the essential goodness of the world.

A letter filled with Gila dust, a breakfast of dried apricots. The droning voice of a blowhard doctor, which one might tolerate in exchange for a decent, undemanding job. In moments like these, the archive of the government’s crimes stirs to life—smuggled proof, for those who need it, that Japanese Americans lived and loved, wanted and wondered, no different from anyone else. Like the work of Dorothea Lange, or of the many other WRA photographers who labored to document incarceration and resettlement Patterson’s writing in this newsletter dances a line between propaganda and subversion.

Reading this newsletter, I can’t help but love and hate him at the same time, this admirable man who dedicated himself to helping others. His delicate, compassionate prose humanizes his subjects, but why do they need humanizing?

* * *

* * *

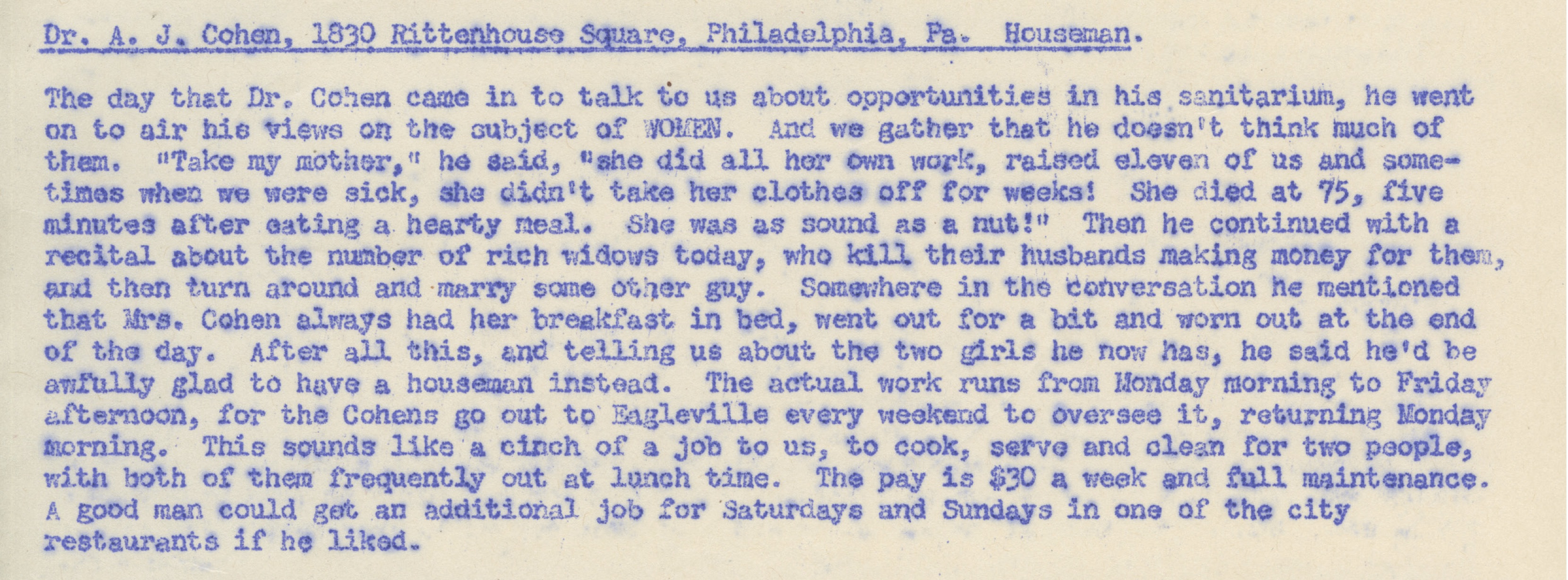

Patterson’s newsletter combines deft anecdotes of resettler life with listings of jobs available to new arrivals from camp—mostly housework, though there are scattered for doctors, nurses, workers at a tuberculosis sanitarium, and even a piano teacher. These aren’t want ads so much as character sketches, full of droll detail and wry editorializing. And the names!

There’s a Mrs. Joseph Scattergood, Jr., of West Chester, “an attractive young woman in her middle thirties” who “married quite a successful doctor.” Alas, she was “terribly distressed” when the marriage produced no children—never to worry, the Scattergoods adopted a matching pair: “a little girl and a little boy, who, when Mrs. Patterson last saw them, looked like picture-book youngsters.” She seeks an “experienced cook-housekeeper.”

Or there is the staid, practical Mr. James C. Butt, officer of the Girard Trust Company in Philadelphia, who requests “two couples for general housework,” one for his own suburban household and one for a neighbor. His correspondence is directed to a P.O. box.

Mr. James T. Haviland, “a prominent somebody whose name often appears in the papers,” seeks “a couple or a girl for general housework.” Mr. Walter Fleischauer, of H.J. Fleischauer’s Sons, Printers, wants “three boys for press feeding,” offering 30¢-50¢ an hour, depending on experience. “Sounds pretty poor to us, but we thought we would tell you about it,” Patterson notes dryly.

By contrast, there is Mrs. Ralph Prewett, “a very charming young woman from Kentucky, with nice manners and a beautiful manner of speech,” who seeks a live-in houseworker at $15 a week: “We like her.”

At times, Patterson gestures at the choking desperation beneath this upper middle-class domesticity, as in the case of the hapless Mr. E.B. Rickard of the Securities and Exchange Commission, “another of these men in a Government office who writes us that his wife is in need of a complete rest and must be relieved of all household duties for a year or two.” Their “three well behaved children” have been removed to “some relatives in the Middle West”: “As soon as possible, he wants to bring the children home.” Who better to care for them than an equally well-behaved refugee?

At times he makes his own judgments evident, as in the case of the opinionated Dr. A.J. Cohen:

Then there is Mrs. J. Robert James, a member of the Quakers’ “Race Relations Committee,” who is looking for a “general houseworker who can cook.” A nurse before her marriage, Mrs. James was board president for a Quaker school when a “colored doctor and his wife” sought admittance for their son; despite “a great loss of pupils,” she and the board stood by their decision to accept the boy, Patterson notes with pride.

I want to honor Patterson, and also to do violence to the smug assurance of his affable prose, aware that my reaction is every bit as unfair as a world that, his newsletter tells us, is just so full of happiness, if you’ll only reach out your hands and grab it.

* * *

* * *

Early in the newsletter, Patterson recounts the conversation of a small group of resettlers and their newfound friends, which includes one Kay Yamashita, who was formerly incarcerated at Heart Mountain and is now working for the NJASRC. The group is discussing the various housing options—hostels, hotels, boarding houses—best suited to those escaping from camp.

Asked her opinion, Kay tactfully defers to the presence of Miss Marian Lantz, director of the International Institute, and insists that she hopes resettlers find a home the institute is providing her. Pressed further by Patterson, Kay adds that “a restful and attractive living room” would be nice.

Another woman concurs, enthusiastically: “you want just what the soldiers want when they come out on furlough—to feel think carpets under your feet, and everything so attractive that you quite forget what camp looked like.”

“Kay nodded reflectively,” Patterson relates, and he gives her the last word: “I should say it would be just perfect if you could work in the city and at night get out to the suburbs where it’s so beautiful and quiet.”

There, in miniature, is the liberal dream of resettlement. The nisei, capable but self-effacing, could leave behind the segregated world of old California, ushered quietly into the promise of a better life—everything so attractive that you quite forget what camp looked like.

The postwar era’s American Dream, a good job in the city and a suburban home, would be established through a liberalization of white supremacy. The legal apparatus of Asiatic exclusion, central to the prewar racial order on the West Coast, would be dismantled, for it was a hindrance to the expansion of US global power in Asia through cold and hot wars. So too was Jim Crow segregation in the South, but as federal support for the latter waned, white flight accelerated in Northern and Western cities. Within two decades, those cities would burst into flames, and the always precarious, always vulnerable second-class status of “model minority” would conscript Japanese Americans as a counter-example to African American protest.

But where did Kay’s fantasy of suburban living come from? From her undergraduate years at Berkeley, from the bitter days in camp, or from her gleaming new life in Philadelphia?

* * *

* * *

Did Henry Patterson harbor a secret desire to become a novelist, or was he satisfied exercising his literary talents as an indulgence in his humanitarian work? I don’t know, but it does so happen that an actual novelist, of great talent and accomplishment, would attempt to do justice to Kay’s wartime experiences, some three-quarters of a century later.

The archives that give rise to Letters to Memory, Karen Tei Yamashita’s genre-bending 2017 reflection on her family’s wartime and postwar experiences, begin in the fourteenth-floor apartment of her recently deceased aunt, with two manila folders containing her personal correspondence and records of her work on behalf of student relocation.

According to Yamashita, her aunt Kay was intensely proud of her adopted hometown of Chicago, and the chic urban identity it signified for her. So much so that, in retrospect, her death seemed tragically fitting: packing her belongings to move to a California retirement community, she had a sudden stroke, fell into a coma, and died.

Never to leave the city, never to leave the new life she had found for herself, washed ashore at the edge of a vast lake, on the far side of camp.

* * *

* * *

He could tell the new arrivals, because they always asked about his sister. You could tell who they were anyway, by the dust that still clung to their scalps, nestled under their fingernails, and irritated their eyes. The boy and his mother were no longer new arrivals, and when it became clear that they had overstayed their welcome, a quiet word from one of the older women and a strapping, blandly innocent young student sent by the WRA man brought them to another boardinghouse, further out into the city.

They still went back to the hostel at least twice a week. At the socials, his mother, shy and troubled, rarely spoke more than was necessary to put conversation to a close. Maybe she was one of those nisei who disliked the company of other Japanese Americans, while craving the recognition, which only they seemed to give, that she was still a human being. Or maybe she just needed a line on better work and a better place to live, but didn’t know how to ask.

Following her lead, the boy avoided talking to the other children at the hostel’s events, but the other kids would talk to him anyway. He didn’t notice that he was the only one who was served a second cookie until they asked him why he ate his own and then was eating hers.

Actually, they didn’t ask, they just scolded him, loud enough for the parents to hear. There was a rushing moment of confusion, as the woman handing out the treats tried to understand why the other adults saw one child where she and the other children had seen two.

He hurried out of the room, and left the remaining cookie, missing one bite, on the small stand by the window. He was not surprised to find it gone when he returned.

* * *

* * *

A separate group of over sixty hostels opened on the West Coast from January 1945 on, after formerly restricted areas were reopened to Japanese Americans, and pressure to empty the camps intensified. And then there were the housing projects, decommissioned army barracks, and trailer homes, hastily established for the last group of incarcerees, who had nowhere to go, and found themselves forcibly removed yet again, leaving their concentration camps to find living conditions that were sometimes even worse.

This other history of resettlement will have to wait for another time. For the first group of hostels could feel like something from a dream.

* * *

* * *

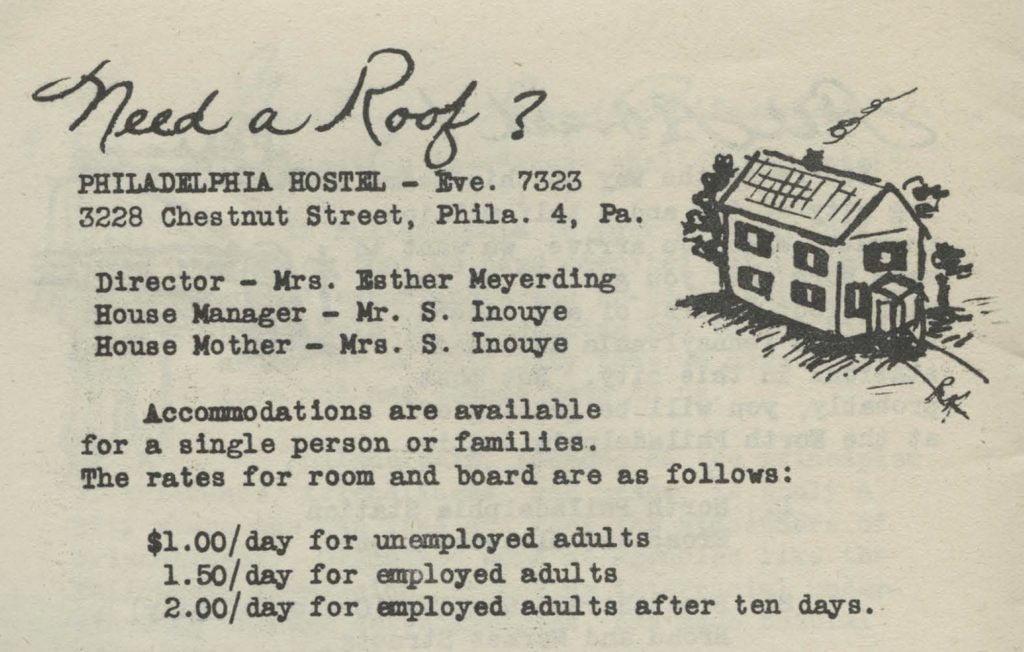

Adult guests at the Philadelphia Hostel paid a dollar a day until they found work, then another fifty cents a day on top of that. It was fifty cents more for a child, and another dollar-fifty for an overnight visitor. After ten days, the rate for employed adult guests went up to two dollars. The camps were emptying, the space was needed, and the wartime city was full of opportunity! Dillon Myer, the WRA director who went on to a postwar career at the Bureau of Indian Affairs, famously worried that his camps and reservations would breed a hapless class of government dependents.

No rate was listed for adult guests still unemployed after ten days in a 1945 WRA pamphlet largely produced by the resettlers themselves. Guests were also expect to contribute to the housework, which was done on a cooperative basis, and encouraged to “talk over problems” with their “houseparents,” Saburo and Michiyo.

After securing more permanent housing, resettlers were welcomed back to the hostel for a variety of events—Sunday open-house teas, Friday night socials, and more edifying programming on Thursday evenings. As another WRA pamphlet explained, “On Thursday nights hostelers, other resettlers, and Caucasian friends assemble to attend informal discussion meetings which are addressed by guest speakers.”

Though presumably the writer for this pamphlet did not intend to imply that nonwhite friends of the nisei and issei would be excluded, it is true that the ideology of resettlement imagined the process as an unequal relation between Japanese Americans and white benefactors.

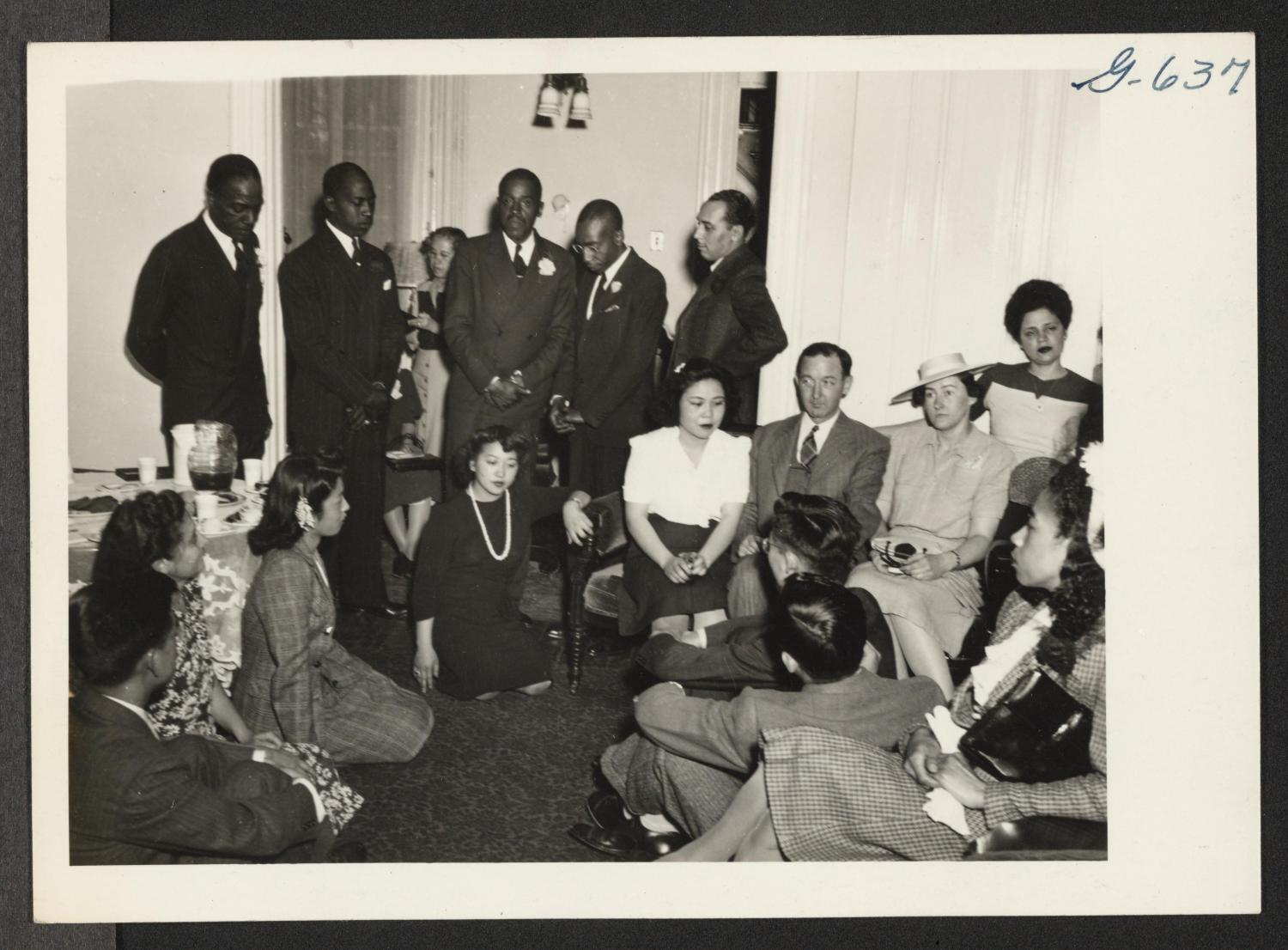

The WRA photo of one social, dated July 8, 1944, does show a group of elegantly dressed black visitors at the Philadelphia Hostel. The caption explains: “During a social at the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Hostel, this group of resettlers and Caucasian friends listens to spirituals sung by the Dewey Wright Quintette of Philadelphia.” Despite the implied color line between performers and audience, the photo shows seated black women listening, as well as the five men in suits.

Most of the nisei in the photograph are sitting or kneeling on the floor, politely ceding the furniture to their white and black guests. Curiously, they form a circle which excludes the five standing men, who are not singing but holding their own hands, heads bowed as if waiting for a prayer to end, save for one who gazes sternly past the camera.

Before camp, Japanese Americans from the larger West Coast cities typically lived in neighborhoods that abutted or overlapped those of African Americans and other people of color, fellow victims of restricted covenants and other forms of housing segregation. Resettlers also faced housing segregation, causing much anxiety for the WRA, which had lectured their wards against the dangers of forming new Japantowns. In Chicago, an existing, segregated black population was swelling rapidly due to wartime arrivals from the South, and the engineers of resettlement made a concerted effort to differentiate the public image of the nisei from their fellow migrants.

No one in the photograph is making eye contact with anyone else.

* * *

* * *

What is the cause of all this mischief?

Someone has been tearing sheets from tablets of paper. Folded airplanes sail out from rooms meant to be unoccupied, the windows left open for the crows to hop through.

Dried apricots go missing, and are found later, half-chewed, behind the sofa. Pennies roll across hallways and clatter down the stairs at odd hours of night.

There is dust everywhere and in everything. The new arrivals scrub and scrub it away mindlessly, a reflex left over from camp, and it’s only weeks later, warm in bed in their new apartments, that they stop to wonder where all that dust came from.

* * *

What kind of women would send their sister a letter filled with dust? What was the message they intended? What message did she receive?

* * *

An entry in the April 1945 “Nisei Date Book,” a monthly list of upcoming events of interest in Penn Notes, a newsletter published by Philadelphia nisei out of the International Institute, advertises a two-day conference on “Quakerism, What It Means to Us as Individuals,” featuring a talk by the writer Jean Toomer, author of the classic Harlem Renaissance novel Cane. While it seems likely that at least a few resettlers may have attended, it’s also possible that they would not have known that Toomer—a mysterious and grandiose figure who is reputed to have sometimes passed for white, and who passed through a variety of radical and mystical circles before becoming a Quaker—was a black man.

* * *