by Tamiko Nimura

As a Sansei, I’ve been exploring the issue of “family separation,” given the multiple ways that families are being separated due to unjust border policy, travel bans, and mass incarceration. I’m currently writing a family memoir that responds to (and includes passages from) my Nisei father’s unpublished memoir of his wartime imprisonment in Tule Lake. The following is a draft from one of the sections of the memoir.

* * * * *

1. I Go Back To My Grandfather, My Father And His Family, Separated In Tule Lake*

The agent said, “Say your goodbyes quickly.”

Without hesitating Father went to Hisa and told her, “Don’t worry.”

Then he walked over to Nob and shook his head, “Watch after your mother.” When he said that my crying turned to deep racking sobs. Nob had tears in his eyes too. Sadako and Tomiye didn’t understand what was happening, but they were crying too, I guess because they saw all of us crying. Father put his hand on my shoulder and wordlessly said his goodbyes by gently shaking me. Father next picked up [baby] Shinobu and rocked her and then put her in my mother’s arms. Then he gathered his gear and waved goodbye to the rest of the family. Tomiye grabbed for his legs, but he gently warded off her arms. Meanwhile, Mother went to the family altar and prayed while tears streamed down her face. Father left the room with the agent.

2. I Go Back to Tule Lake With My Father

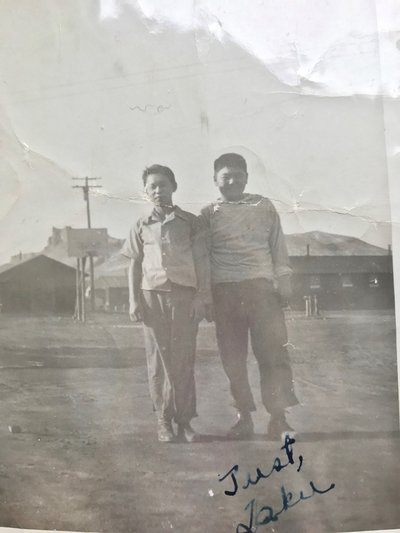

Last year, I saw this picture of my father for the first time. It was waiting for me in my oldest auntie’s scrapbook.

It is the only picture I have ever seen of my father in camp. He is about 12 years old here.

3. I Draw New Mental Maps

I begin to draw new lines, add new pins on the maps in my head. The maps reconfigure themselves into an atlas of incarceration, displacement, and home.

4. I Go Back to California

California, where my sister and I grew up.

Arboga: At ten years old, our father and his family were taken to Arboga, the “assembly center,” where the heat was so extreme that they tried to keep their barrack doors open but were soon pursued by the mosquitoes and insects next to the communal latrine. Maximum population: 2465.

Tule Lake: Maximum population: 18,789. After Arboga, the government transferred our father and his family to Tule Lake, built on the ancestral lands of the Modoc Tribe. When recruiters for the military draft came to Tule Lake, our grandfather spoke out several times in public against the draft, arguing that the government had stripped Nisei of their citizenship rights. For speaking out, the government took him away from his family and imprisoned him in Sharp Park, California (maximum population: 379). When he refused to recant his statements, they imprisoned him in Santa Fe, New Mexico (maximum population: 2,100). From one prison to another to another.

5. I Go to Texas

Austin: where my sister and her family live.

Austin: In 2018, Home base of nonprofit Southwest Key, responsible for running 26 detention facilities for minors in the United States. Site of the first lawsuit filed on behalf of Central American asylum seekers challenging the “zero tolerance” policy, enabling family separation at the United States/Mexico border.

Crystal City: “U.S. Family Internment Camp,” where internees of Japanese, Latin America, German, and Italian descent were imprisoned. Maximum capacity: close to 4,000 persons in December 1944.

Dilley: Current site of the “South Texas Family Residential Center,” where detainees are seeking asylum in the United States from South America. Current population: 2400, mainly mothers and children.

6. I Go Back To My Six Year Old Aunt In Tule Lake

Tomiye for one seemed to miss Father. She was now six years old. She wandered around the barrack rooms in search of him. We tried to tell her that he was gone, but she kept right on looking for him. It was as if Tomiye thought Father was playing hide and seek and would suddenly reappear.

7. I Go Back To My Twenty-Year Old Auntie Trying To Find My Grandfather From Tule Lake

March 9, 1943

District Director San Francisco Director

U.S. Department of Justice

Immigration and Naturalization Service

San Francisco, California

Dear Sir:

My father, Junichi Fred Nimura, family number 25401, was recently removed from Tule Lake by the FBI. May I know where he is? How long will he be gone? May we write to him? Can we send him some toilet articles and additional clothing? Will my father return to Tule Lake soon? Any information about my father will be greatly appreciated.

Sincerely yours,

Hisa Nimura

8. I Go Back To My 13 Year Old Father Leaving Tule Lake Without My Grandfather

We were the only family headed for Placer County.

…

It was getting closer to departure time and by now Mother and the rest of the children except me were crying. Relocation was difficult at best, but with the added burden of doing it without my father was almost too much for me to bear.

By this time, I was gritting my teeth and straying from the family circle. I was trying to show the family that I was ready to take on the world. I was more than determined in my own mind not to cry this day. I kept busy, playing head of the family by checking the hand luggage and fussing with packages. Father understood why I was acting the way I was.

Father turned from me and walked quickly toward the main gate. He passed the double set of barbed wire fences and turned the corner. I wanted him to turn around and wave goodbye to me, but Father was wise; he didn’t look back….At first I felt a lump in my stomach. Then the lump reached my throat and by the time it reached my mouth, I was sobbing uncontrollably. It was a deep anguished cry as if I were in severe pain. I tried not to cry, but the tears would not stop. I fought the tears and that only made it worse. My ribs began to ache and still I cried…..

I felt bitter then. I didn’t know where to direct my bitterness.

9. I Am Here in Washington

Tacoma, where my family and I live. Ancestral land of the Puyallup Tribe.

Division Avenue, Tacoma. Site of official-and-then-unofficial redlining, where people of color were restricted from renting or owning property for decades.

Pierce County Main Jail, Tacoma. Population for July 2018, average: 570.

Union Station, Tacoma. In 1942, on the authorization of Executive Order 9066, over 700 Japanese Americans were forced to leave their homes in Tacoma and boarded a train for Pinedale, California.

Chinese settlement, Tacoma. In 1885, a group of men from Tacoma rounded up approximately 200 Chinese residents of Tacoma, marched them out of town, and burned down their shops and homes. The event became known nationally as “The Tacoma Method.”

Puyallup, neighboring town to Tacoma. Ancestral land of the Puyallup Tribe. Site of the Cushman Indian School built in 1860, where hundreds of Native children were forcibly separated from their families for decades.

McNeil Island Penitentiary, just south of Tacoma. Japanese American wartime draft resisters from Heart Mountain, Wyoming sent here after sentencing. Gordon Hirabayashi, resister of conscience, spent time here.

Camp Harmony. Built on Puyallup tribal lands and the Washington State fairgrounds as an “assembly center” in 1942. Maximum population: 8,000 Japanese Americans.

Northwest Detention Center. Current site of the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), privately operated by the GEO corporation. Number of hunger strikes conducted to improve living conditions for detainees: at least 3 in 4 years. Current population capacity: 1575.

10. I Recalculate Home and Distance

I calculate new distances.

Home to Arboga: 680 miles.

Home to Tule Lake: 450 miles.

Home to Sharp Park: 790 miles.

Home to Santa Fe: 1200 miles.

Home to Division Avenue: 4 miles.

Home to Union Station: 5 miles.

Home to the former Chinese settlement: 3 miles.

Home to Puyallup: 15 miles.

Home to Pierce County Jail: 2 miles.

Home to McNeil Island Corrections Center: 10 miles.

Home to Northwest Detention Center: 6 miles.

Me to my daughters in their bedrooms: 15 feet.

All distances approximate.

Home.

*All italicized text is from my father Taku Frank Nimura’s unpublished book manuscript, “Daruma: The Indomitable Spirit” (c.1973).

Also Published at “DiscoverNikkei.org, a project of the Japanese American National Museum”, August 2018.